I am a writer and editor with more than 15 years of professional experience. A graduate of Yale University (BA in English Literature) and Johns Hopkins University (MA in Creative Writing), I was awarded the James Ashmun Veech Prize for most imaginative undergraduate writing by the Yale College English Department. I also attended the Radcliffe Publishing Course and have been published in a variety of magazines and newspapers including the Yale Daily News, Kennedy Center Stagebill, Entertainment Weekly, the Washington Post, and The Smithsonian Magazine.

Digital writing and editing samples

WRITING/CONTENT CREATION SAMPLES:

Created all content on the following sites (wrote all copy and selected all images)

An Evening with Novelist Min Jin Lee (Eventbrite event listing)

Yazidi Women: The Road to Recovery (Eventbrite event listing)

Justice for Yazidis (website for survivors of Yazidi genocide)

Justice for Yazidis Resettlement Petition (online petition)

Fact Sheet on U.S. Resettlement (for DHS officials on behalf of OIF translators)

Ending the War (original writing on resolutions in Afghanistan)

Solar Farms (article written for Conservation Nebraska website)

Advocacy for Ms. Sherin Jardo (summary of pro bono advocacy work completed in 2020)

COPYEDITING SAMPLE:

How To End America’s Longest War (policy brief copyedited and proofread)

Print writing samples

Once in a Hundred Years

from Kennedy Center Stagebill

Written by Taehee Kim

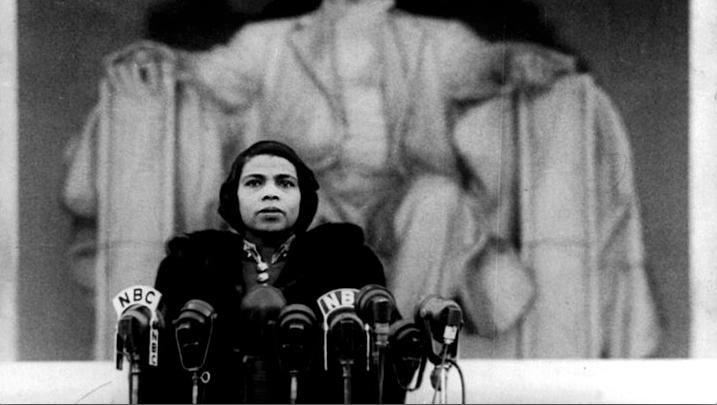

In 1939, on a clear, chilly Sunday in the nation’s capital, a remarkable singer faced an audience from an unusual stage. Standing before the pale gray marble steps and giant colonnades of the Lincoln Memorial, the woman peered at the surging crowd of 75,000 as she took a breath and launched first into “The Star-Spangled Banner” and, later, Franz Schubert’s tender “Ave Maria.” The singer was Marian Anderson, the subject of the Kennedy Center-produced My Lord, What a Morning: The Marian Anderson Story. And by singing at the Lincoln Memorial that April afternoon, the black woman who earlier had been unable to perform at Daughters of the American Revolution Constitution Hall because of the color of her skin was making a quiet but powerful stand in the country’s struggle for racial equality.

“What we wanted to do was to introduce young audiences to Marian Anderson as an extraordinary individual and an extraordinary artist,” says Derek Gordon, the Kennedy Center’s Vice President for Education, who began work on commissioning a piece based on the life of the singer after reading an article about her historic performance in the New York Times several years ago. “Today she’s widely recognized as a figure in the Civil Rights movement, but when [manager and impresario] Sol Hurok was trying to book a concert for Anderson at DAR Constitution Hall, it was because of her voice, because of her artistry.”

The voice, Gordon notes, even managed to astound the likes of conductor Arturo Toscanini, who once said: “You possess a voice one hears once in a hundred years.”

It was not an easy road that led from Anderson’s hard-working, church-centered community in Philadelphia, where she was born in 1902, to the finest concert halls of Europe and to international acclaim. As a young woman, Marian Anderson’s hopes of becoming a trained singer suffered cruel setbacks: the musical conservatory she wished to attend would not take applications from “coloreds.” Despite lifelong battles against such racial bigotry, Anderson rose to prominence, eventually studying with the most respected voice teachers in the world.

In 1955, her aspirations made musical history when Anderson became the first African-American singer to perform with the Metropolitan Opera. No black artist had sung with the Met since its founding in 1883, and, as usual, Anderson’s appearance turned into headline-making news. In the New York Times, an editorial read: “That Marian Anderson has fulfilled a lifelong ambition is not nearly as important as the fact that we have another opportunity to hear her in still another medium. When there has been discrimination against Marian Anderson, the suffering was not hers, but ours. It was we who were impoverished.”

Praised by Eleanor Roosevelt for her “magnificent dignity as a human being,” Anderson had been the first black singer to perform at the White House in 1936, at the personal invitation of President and Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt. Later, she was chosen to serve as a U.S. delegate to the United Nations by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Her role as Ulrica in Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Un ballo in maschera at the Metropolitan Opera not only made classical music history, it also paved the path for other black singers to appear at the Met, such as Robert McFerrin and Leontyne Price.

In the Kennedy Center’s production of My Lord, What a Morning, playwright Kim Hines uses various narrative techniques to offer insight into the human being as well as the artist. “I wanted to have two characters onstage at the same time—-the young, less experienced Marian Anderson and the older, wiser Marian Anderson—so that the older woman could offer advice to the younger singer in terms of what she could have done differently, what she could have done instead.” It was one way, says Hines, “to look at her as a person, and not just as a civil rights figure.”

In the face of subtle and not-so-subtle prejudice and racial animosities, Anderson remained true to her art and became a legend in the process. After a lifetime of achievement, she was able to reflect in her autobiography on the folly of judging men and women on the color of their skin. “If one searched one’s heart one would know,” she wrote, “that none of us is responsible for the complexion of his skin, and…that this fact of nature offers no clue to the character or quality of the person underneath.”

Michael Apted: Starting “Up”

from Entertainment Weekly

Written by Taehee Kim

His feature films (Coal Miner’s Daughter, Gorillas in the Mist) may be better known, but some of British director Michael Apted’s most revelatory screen adventures have happened far from the Hollywood mainstream. Starting in 1963 with 7 Up, a British TV program on the lives of 14 English schoolchildren, Apted has revisited his subjects every seven years to produce an engrossing series about the mysteries of growing up. While the second and third installments were well received in England, Apted says the series “only got really good” with 28 Up, the 1984 award-winning documentary released on video this week.

The project began when Apted, straight out of Cambridge University (where he studied law and history) got a job as a researcher, assigned to knock on doors of public and private elementary schools and look for suitable 7-year-olds to interview for 7 Up, a deeply critical look at the inequalities of the English class and education system. Seven years later, at a friend’s casual suggestion, Apted turned the one-shot 7 Up into an ongoing experiment, this time not as a researcher but as a director. By now, Brits have been following the lives of 7 Up’s cherubic youngsters for the past 28 years (the latest installment, 35 Up, was broadcast in Britain this year and has not yet found theatrical distribution in the United States).

Reached by phone on the set of his feature Thunderheart, a contemporary thriller set on a Native American reservation, Apted recalls the special resonance of his latest visit to his subjects in 35 Up: “What moved me the most was that a lot of them had children the same age as when we started, so you see the circle completed—you can see them handing on the wisdom that we’ve watched them acquire.”

While tracking down the subjects is relatively simple (“England is a fairly small country”), cajoling them into sharing their personal lives with the camera is not so easy. “It’s such an invasion of privacy for them,” says Apted, 50, who lost three of the original 14 participants after they refused to be filmed.

Meanwhile, the seed of Apted’s original brainchild has been planted in other countries: an American version of 7 Up, directed by Phil Joanou (U2: Rattle and Hum) and produced by Apted, will air on CBS next season, with plans for ongoing updates. Like the original British version, Joanou’s documentary (called Age 7 in America) shows children from all walks of life-—three little girls from an Upper East Side private school are profiled along with a young boy living in a shelter for the homeless-—but it is decidedly more ethnically diverse. “I’m sorry there wasn’t more ethnic diversity in the English one,” says Apted, whose only black participant, Symon, refused to be filmed in 35 Up. “I’m sorry there weren’t more women in it as well.”

A similar project is also under way in the Soviet Union (with Apted serving as a consultant), and there are tentative plans to launch Japanese and German versions. What’s giving directors the seven-year itch? For Apted, the appeal is simple: “It’s a very

entertaining, personal, and accessible way of dealing with change.”

Les Compagnons: “I owe them a lot; they taught me the love of work”

from Smithsonian Magazine

Online abstract written by Taehee Kim

From boilermaking to fixing up an angel’s wing, Les Compagnons hone marketable skills in a medieval brotherhood brought up to date…

They have painstakingly restored the towers of Notre Dame, sandblasted grime off the Arc de Triomphe, helped build the new transparent entryway pyramid to the Louvre. In 1984, they even crossed the Atlantic to restore the badly corroded torch on the Statue of Liberty to its former glory. Who are these craftsmen, of such valuable and impeccable skills? They are les compagnons (the companions), members of French craft guilds that can trace their lineage to traditions dating back to the Middle Ages.

In a country where unemployment runs close to 25% among the young, these stonemasons, metalworkers, carpenters and chocolatemakers (among dozens of other trades) have no difficulty finding work. Says one guild official, “They’re snapped up by employers as fast as we can train them.”

Starting their training as early as age 15, aspiring Compagnons study for two years under the auspices of a local firm, after which they embark on the ultimate adventure: the Tour de France. Described by novelist George Sand as a “poetic phase, an adventuresome pilgrimage, the artisan’s period of errant knighthood,” the Tour is a 6- to 8-year trek across France in which guildsmen concentrate on their trade. Working one-on-one with master craftsmen, the young aspirants are expected to develop their moral character as they refine their trade skills. According to medieval tradition, aspiring Compagnons stay celibate during their tour, and women are still prohibited from being initiated into the compagnonnage, an exclusivity that continues to provoke spirited debate.

# # # # #